ONE of the major limiting factors in flight is the need for such heavy equipment as a power plant and coal bunkers, sails, or galley cranksmen. The fact that such mechanisms might one-day be discarded has received remarkably little attention.

|

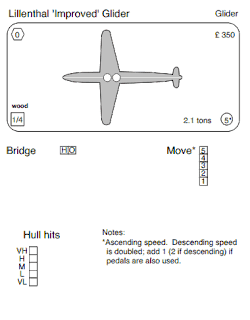

| One of Lilienthal's 19th C. gliders. |

Recent experiments with winged heavier-than-air gliders have established that it is possible to build a craft capable of attaining respectable speeds by trading height for velocity. It may even be possible to take advantage of 'thermals' and other upwards air currents, familiar to anyone who has ever traveled by flyer, to regain height. Naturally, such craft must eventually land, but some remarkable results have been achieved, most notably by the late Sir George Caley and more recently by the German engineer Otto Lilienthal.

Liftwood panels would allow gliders to maintain their speed while gaining height, and thus stay aloft indefinitely. Headway would only be lost if the craft attempted to maintain constant altitude, and it might be possible to use a foot-pedaled airscrew for this eventuality. Such a craft would look radically different from our current flyers, much more like the winged aircraft envisioned by Da Vinci. It has the potential to be as fast as any steam flyer in service today.

It would be wrong to suggest that there are no drawbacks to this idea. A craft that must constantly change altitude might induce nausea in its passengers. The degree of such sickness would, of course, relate to the frequency of such altitude changes; it has seldom been reported by users of conventional gliders, who rarely experience anything other than a slow descent, and occasional broken limbs. More seriously, constant altitude changes and the need for extensive streamlining would make gliders a poor mount for artillery and other weapons, and it might cause stresses, which would limit their cargo capacity.

Putting these facts together, the most likely use for such a craft would be as a courier or as a fast, maneuverable and almost completely silent scout, possibly launched from a larger vessel, capable of carrying a helmsman (who also operates the trim controls) and one or two observers. The amount of liftwood built into the craft could be remarkably small compared too that needed for a normal flyer; once it is moving at any speed, air flowing over the wings should provide considerable upthrust. In flight the liftwood would mainly provide the extra impetus need to gain height after each descent, a relatively small amount of the force. Since the liftwood would not be the sole support of the craft, trim errors would be considerably less important than in a conventional flyer, giving the helmsman ample time to compensate before they become critical.

In the long term, it is possible to envisage a hybrid craft combinine the best features of the liftwood flyer and the glider, capable of high speeds and perhaps carrying several tons of cargo. But perhaps such wild speculation is best left to the writers of scientific romances and their readers…

About the Author

Marcus Rowland is a London based laboratory technician and the author of Canal Priests of Mars and other material for Space 1889. He has also written numerous other adventures and articles, as well as the role-playing game Forgotten Futures, a series on disk that is distributed as computer shareware.

by Marcus L. Rowland, ©1990. Fuelless Flyers originally appeared in a British game shop newsletter. It is used here with the permission of the author.

Related Article:

No comments :

Post a Comment